Introduction to Datalog

Overview

Datalog is a (declarative) logic-based query language, allowing the user to perform recursive queries. It adopts syntax in the style of Prolog. In its pure form, it is based on a decidable fragment of first-order logic (FOL). Here, the universe – the collection of elements by which computation can be performed within – is finite, and functors are not permitted. Applications of Datalog include program analysis, security, graph databases, and declarative networking.

Soufflé: The Language

Motivation

The syntax of Soufflé is inspired by implementations of Datalog, namely bddbddb and muZ in Z3.

There is no unified standard for the specification of Datalog syntax. Thus, each implementation of Datalog may differ.

A principle goal of the Soufflé project is speed, tailoring program execution to multi-core servers with large amounts of memory.

With this in mind, Soufflé provides software engineering features (components, for example) for large-scale logic-oriented programming.

For practical usage, Soufflé extends Datalog to make it Turing-equivalent through arithmetic functors.

This results in the ability of the programmer to write programs that may never terminate.

An example of non-termination is a program where the fact A(0). and rule A(i + 1) :- A(i). exist without additional constraints. This causes Soufflé to attempt to output an infinite number of relations A(n) where n >= 0.

This is in some way analogous to an infinite while loop in an imperative programming language like C.

However, the increased expressiveness afforded by arithmetic functors is very convenient for programming.

First example

Soufflé supports UNIX, FreeBSD, Mac OS X and Windows, and can be installed as per these instructions.

Soufflé is invoked by command line in the format souffle <flags> <program.dl>, where <program.dl> is the input program that is to be evaluated.

The input fact directory is set with flag -F <dir>, specifying the input directory for relations. The default directory is the current directory.

The output directory for relations is set with flag -D <dir>, and also defaults to the current directory. Note that if <dir> is set to -, the output will be written to stdout.

Transitive closure

A relation R on a set X is transitive if, for all x, y, z in X, whenever x R y and y R z then x R z. In the example below, we consider a directed graph, where edges define relations, and a tuple is in the transitive closure (the reachable relation) if it satisfies either of the two rules below.

.decl edge(n: symbol, m: symbol)

edge("a", "b"). /* facts of edge */

edge("b", "c").

edge("c", "b").

edge("c", "d").

.decl reachable (n: symbol, m: symbol)

.output reachable // output relation reachable

reachable(x, y):- edge(x, y). // base rule

reachable(x, z):- edge(x, y), reachable(y, z). // inductive rule

Indeed, all elements in edge are in reachable (by the base rule), and the inductive rule captures the transitive property, including tuples like reachable("a", "d").

- Extend the previous code to add a new relation SCC(x, y), that is defined as: if node x reaches node y and node y reaches node x, then (x, y) is in SCC.

- Check whether a node is cyclic.

- Check whether the graph is acyclic.

- Omit the flag `-D-` - where is the output?

Same generation example

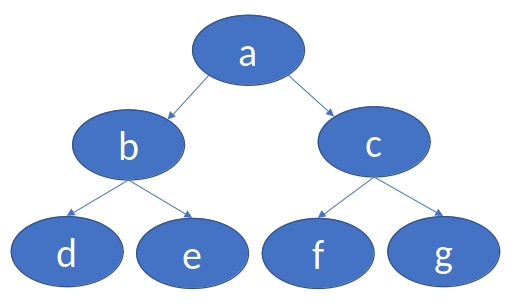

Given a tree (a directed acyclic graph with a particular root node), the goal is to find which nodes are on the same level.

In the above graph, nodes b and c are on the same level, as are nodes e and g.

.decl Parent(n: symbol, m: symbol)

Parent("d", "b"). Parent("e", "b"). Parent("f","c").

Parent("g", "c"). Parent("b", "a"). Parent("c","a").

.decl Person(n: symbol)

Person(x) :- Parent(x, _).

Person(x) :- Parent(_, x).

.decl SameGeneration (n: symbol, m: symbol)

SameGeneration(x, x):- Person(x).

SameGeneration(x, y):- Parent(x,p), SameGeneration(p,q), Parent(y,q).

.output SameGeneration

Data-flow analysis example

Data-flow analysis (DFA) aims to determine static properties of programs. DFA is a unified theory, providing information for global analysis about a program. DFA is based on control flow graphs (CFGs), where analysis of the program is derived from properties of nodes and the graph.

An example is a reaching definition - that is, whether a definition of a variable reaches a given point in the program. Note that an assignment of a variable can directly affect the value at another point in the program.

To cope, we consider an unambiguous definition d of a variable v as defined as follows:

d: v = <expression>;

Then, a definition d of a variable v is considered to reach a statement u if all paths from d to u do not contain any unambiguous definition of v. We note that functions can have side effects to variables even in the absence of explicit unambiguous definitions.

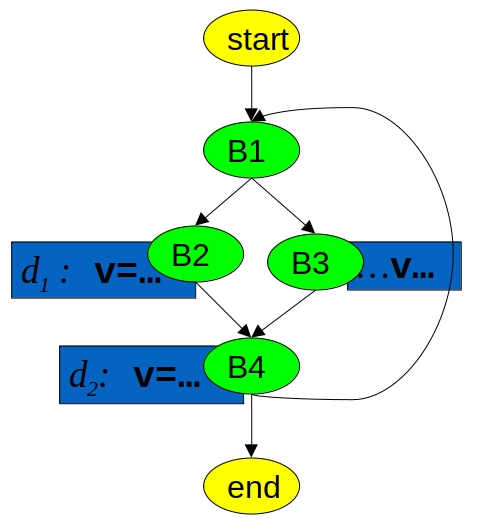

Consider the following control flow graph:

The above example contains unambiguous definitions d1 and d2 of the variable v. By inspection, we see that B3 can only be reached when v is defined as per d2. The following code outputs all stages of the CFG where v is possible captured by one of these definitions.

// define control flow graph

// via the Edge relation

.decl Edge(n: symbol, m: symbol)

Edge("start", "b1").

Edge("b1", "b2").

Edge("b1", "b3").

Edge("b2", "b4").

Edge("b3", "b4").

Edge("b4", "b1").

Edge("b4", "end").

// Generating Definitions

.decl GenDef(n: symbol, d:symbol)

GenDef("b2", "d1").

GenDef("b4", "d2").

// Killing Definitions

.decl KillDef(n: symbol, d:symbol)

KillDef("b4", "d1").

KillDef("b2", "d2").

// Reachable

.decl Reachable(n: symbol, d:symbol)

Reachable(u,d) :- GenDef(u,d).

Reachable(v,d) :- Edge(u,v), Reachable(u,d), !KillDef(u,d).

.output Reachable

Remarks on Input and C-Preprocessor.

Like in C++, Soufflé uses two types of comments:

- Type 1:

// this is a remark - Type 2:

/* this is a remark as well */

C preprocessor processes input from Soufflé. For example:

#include "myprog.dl"

#define MYPLUS(a,b) (a+b)

Relations

Relation declaration

A relation must be declared in order to be able to be used. We briefly note that the order in which lines of code are written in Soufflé code does not impact on a program’s correctness. The statement:

.decl edge(a:symbol, b:symbol)

Declares the relation edge with two fields, a and b, each of which are symbols (strings).

I/O Directives

Users can specify directives for loading input and writing output to a file:

- The input directive

.input <relation-name>reads from the<relation-name>.facts, which is assumed to be tab-separated by default. - The output directive

.output <relation-name>writes to a file, usually<relation-name>.csv(by default) or stdout (depending on options). - The print relation size directive

.printsize <relation-name>prints the cardinality of a given relation to stdout.

The following example illustrates the aforementioned functionality:

.decl A(n: symbol)

.input A // facts are read from file A.facts

.decl B(n: symbol)

B(n) :- A(n).

.decl C(n: symbol)

.output C // output appears in C.csv

C(n) :- B(n).

.decl D(n: symbol)

.printsize D // the number of facts in D is printed

D(n) :- C(n).

Relations can be loaded from/stored to:

- Arbitrary CSV files

- Compressed text files

- SQLite3 databases

For example, to store a relation after evaluation into a SQLite3 database, the user can specify something like this:

.decl A(a:number, b:number)

.output A(IO=sqlite, dbname="path/to/sqlite3db")

More information about the possibilites for I/O can be found in the documentation here.

Lack of goals in Soufflé

A goal in Datalog is a logical relation of the form false <= p, where p is a logical relation.

In the case of Soufflé, goals are simulated by output directives.

The advantage is that several independent goals can be evaluated in a single execution of a Soufflé program.

Syntactic conveniences:

Rules with multiple heads can be written. This is syntactic sugar to minimise coding effort. Here is a code snippet taking advantage of this feature and the equivalent code without the transformation applied:

| Multiple heads | Single head |

|---|---|

|

|

Similarly, disjunctions in rule bodies are permitted as syntactic sugar, such as in the following example:

| Disjunction in rule bodies | No disjunction in rule bodies |

|---|---|

|

|

Type system for attributes

Soufflé’s type system is static, like languages like C and unlike languages like Python. The attributes of a relation must be defined before compilation (or interpretation), and types are checked at compile-time. This supports programmers having a clear idea of the definition of relations and their usage. To minimise evaluation time, no dynamic checks are made at runtime.

Types correspond to the subdivision of elements (relations) and sets of elements over the universe. In particular, a type refers to either a subset of a universe or the universe itself. Elements of subsets are not defined explicitly. As we shall see with union types, subsets can be composed of other subsets.

Primitive types

Soufflé has two primitive types, namely the symbol type symbol and the number type number.

The symbol type comprises the universe of all strings.

Internally, it is represented by an ordinal number.

The value ord("hello") corresponds to this ordinal number for a given program, in this case for the string “hello”.

The number type comprises the universe of all numbers.

Arithmetic expressions

Among others functors, Soufflé permits arithmetic functors, which extend traditional Datalog semantics.

Variables in functors must be grounded for use. That is, they may not contain any free variables.

As described earlier, termination may be a problem as in the case of an imperative while loop.

A basic example is as follows:

.decl A(n: number)

.output A

A(1).

A(x+1) :- A(x), x < 9.

In particular, the second condition in the conjunction on the last line invokes the arithmetic operator <.

.decl Fib(i:number, a:number)

.output Fib

Fib(1, 1).

Fib(2, 1).

Fib(i + 1, a + b) :- Fib(i, a), Fib(i-1, b), i < 10.The following arithmetic functors are allowed in Soufflé:

- Addition:

x + y - Subtraction:

x - y - Division:

x / y - Multiplication:

x * y - Modulo:

a % b - Power:

a ^ b - Counter:

autoinc() - Bit operations:

x band y,x bor y,x bxor y, andbnot x - Logical operations:

x land y,x lor y, andlnot x

The following arithmetic constraints are allowed in Soufflé:

- Less than:

a < b - Less than or equal to:

a <= b - Equal to:

a = b - Not equal to:

a != b - Greater than or equal to:

a >= b - Greater than:

a > b

In source code, numbers can be written in decimal, binary and hexadecimal. Below is an example illustrating such:

.decl A(x:number)

A(4711).

A(0b101).

A(0xaffe).

Note that in fact files only decimal numbers are permitted.

Number encoding

Numbers can be used as logical values, as in C:

- 0 represents false

- != 0 represents true

As such, they can be used for logical operations: x land y, x lor y and lnot x

An example is as follows:

.decl A(x:number)

.output A

A(0 lor 1).

The functor autoinc()

The functor autoinc() issues a new number every time it is evaluated.

However, it is not permitted in recursive relations. It can be used to create unique numbers (acting as identifiers) for symbols, such as in the following example:

.decl A(x: symbol)

A("a"). A("b"). A("c"). A("d").

.decl B(x: symbol, y: number)

.output B

B(x, autoinc()) :- A(x).

.decl A(x:symbol) input

.decl Less(x:symbol, y:symbol)

Less(x,y) :- A(x), A(y), ord(x) < ord(y).

.decl Transitive(x:symbol, y:symbol)

Transitive(x,z) :- Less(x,y), Less(y,z).

.decl Succ(x:symbol, y:symbol)

Succ(x,y) :- Less(x,y), !Transitive(x,y).

.output Less, Transitive, Succ.decl First(x: symbol) output

First(x) :- A(x), ! Succ(_, x).

.decl Last(x: symbol) output

Last(x) :- A(x), ! Succ(x, _).String functors

The usage and characterisation of the string (symbol) functors supported by Soufflé can be found here.

Aggregation

Aggregation in Soufflé refers to the use of particular functors to summarise information about queries.

Aggregates can only be applied on stable relations in Soufflé.

Types of aggregates include counting, finding the minimum/maximum of a set of numbers, and summation.

Generally in Soufflé, information cannot flow from the sub-goal (the argument/s of the aggregate functor) to the outer scope.

For example, if one wishes to find the minimum value of the relation Cost(x), they cannot find a specific value of x that minimises Cost.

Indeed, such a value of x may not be unique.

Counting

The counting functor allows the user to count the set size of a sub-goal.

The syntax is count:{<sub-goal>}.

The following example outputs the number of “blue” cars - that is, the number of elements in Car with second argument “blue”:

.decl Car(name: symbol, colour:symbol)

Car("Audi", "blue").

Car("VW", "red").

Car("BMW", "blue").

.decl BlueCarCount(x: number)

BlueCarCount(c) :- c = count:{Car(_,"blue")}.

.output BlueCarCount

Maximum

The max functor outputs the maximum value of a set.

The syntax is max <var>:{<sub-goal(<var>)>}.

An example:

.decl A(n:number)

A(1). A(10). A(100).

.decl MaxA(x: number)

MaxA(y) :- y = max x:{A(x)}.

.output MaxA

Minimum & Sum

Similarly to the above, these functors compute the minimum/sum of a sub-goal.

The min syntax is min <var>:{<sub-goal>(<var>)>}, and the sum syntax is sum <var>:{<sub-goal>(<var>)>}.

Witnesses are not permitted

Consider the following example which will not compile:

.decl A(n:number, w:symbol)

A(1, "a"). A(10, "b"). A(100, "c").

.decl MaxA(x: number,w:symbol)

MaxA(y, w) :- y = max x:{A(x, w)}.

Here, the user wishes to produce a witness for the maximum value of the first argument of A.

This causes semantic and performance issues.

Semantically, it is not clear what it means to find a witness for the count and sum functors.

In terms of performance, there is overhead.

As such, this kind of code is forbidden by the type-checker.

Records

Relations are two-dimensional structures in Datalog. With a large code-base and/or a complex problem, it can be convenient to consider relations with more complex structure (recursion/hierarchy, etc.). Records provide such an abstraction, breaking out of the flat world of Datalog at the price of performance, due to an additional table lookup required when invoking records. Their semantics are comparable to those in Pascal/C. In future, unions of records will be allowed to simulate polymorphism. The syntax of a Record Type definition is as follows:

.type <name> = [ <name_1>: <type_1>, ..., <name_k>: <type_k> ]

Currently, there is no output facility, but it is planned that Soufflé 2.0 will support this.

In the meantime, this can be simulated by mapping records to relations, where .output can then be called.

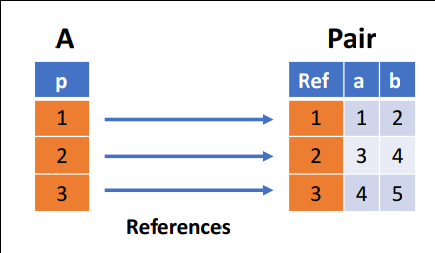

The following example creates a record corresponding to a pair of numbers, in which the Flatten relation can be then be printed.

// Pair of numbers

.type Pair = [a:number, b:number]

.decl A(p: Pair) // declare a set of pairs

A([1,2]).

A([3,4]).

A([4,5]).

.decl Flatten(a:number, b:number) output

Flatten(a,b) :- A([a,b]).

Overview of record internals

Each record type has a hidden type relation. There, elements of a record are translated to a number. During evaluation, if a record does not exist, it is created on the fly. Considering the example as above:

.type Pair = [a: number, b: number]

.decl A(p: Pair)

A([1,2]).

A([3,4]).

A([4,5]).

Internally, these records are represented and stored as per this diagram:

Recursive records

Recursively-defined records are permitted in Soufflé.

The recursion is terminated by the existence of a nil record.

Consider the following:

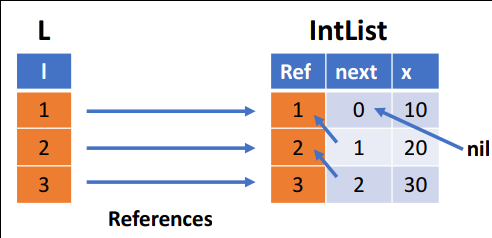

.type IntList = [next: IntList, x: number]

.decl L(l: IntList)

L([nil,10]).

L([r1,x+10]) :- L(r1), r1=[r2,x], x < 30.

.decl Flatten(x: number)

Flatten(x) :- L([_,x]).

.output Flatten

Here, an IntList contains a reference to the next element, which is an IntList itself.

Internally, this is represented as follows:

As before, the Flatten relation allows for output.

The semantics of recursive records are tricky.

Records are relations and sets of recursive elements, which monotonically grow in size over time.

They are equivalent to relations with the use of the nil record.

In the future, polymorphism may be possible at the expense of execution time and space.

Components

Components are defined and showcased in this article.

An interesting exercise for the reader is to develop a library of components for graphs. The library should be extensible and contain various items of functionality, including:

- A component for a directed graph

- A component for an undirected graph

- A component that checks for a cycle in a graph

- A component that checks whether a graph is acyclic.

Performance and profiling facilities

To gain performance in the execution of Datalog program, we can:

- Compile, rather than interpret code

- Schedule queries, through user annotations or automation

- Find faster queries that perform the same desired task

- Find faster data models

To achieve these aims, profiling a given program is paramount. An overview of Soufflé’s profiler, which provides a textual and graphical UI, can be found here.

To compile and immediately execute a Soufflé program, the option -c can be used, e.g. souffle -c test.dl executes the binary produced from the .cpp file produced by test.dl. To just generate the executable, the option -o can be used.

To achieve high performance, the programmer can manually re-order the atoms in the body of a rule. A query plan can also be provided with the following syntax <rule>. .plan{ <#version> : (idx_1, ..., idx_k) }.

An exercise for the reader is to execute the following code, varying the choice of the last three lines each time, and benchmarking using the profiler:

.decl Edge(x:number, y:number)

Edge(1,2).

Edge(500,1).

Edge(i+1,i+2) :- Edge(i,i+1), i < 499.

.decl Path(x:number, y:number)

.printsize Path

Path(x,y) :- Edge(x,y).

// Path(x,z) :- Path(x,y), Path(y,z). .strict

// Path(x,z) :- Path(x,y), Edge(y,z). .strict

// Path(x,z) :- Edge(x,y), Path(y,z). .strict